The Presidential Dairy

William Howard Taft’s prize milker

Cabinet

The eight years of Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency saw the White House occupied by an unprecedented menagerie—from a bear named Jonathan Edwards to Maude the pig; a badger, a lizard, a hyena, a pony, guinea pigs, birds, and numerous dogs, including the famously cantankerous bull terrier known as Fighting Pete, whose penchant for biting visitors’ legs eventually got him exiled to the family’s estate on Long Island. Less zoologically promiscuous than his predecessor, William Howard Taft, who succeeded Roosevelt in 1909, brought with him a rather more modest faunal retinue in the form of a Jersey cow. Mooley, as the animal was known—an alternate spelling of the word “muley,” meaning a hornless cow—was allowed to graze on the White House lawn and the Ellipse (then known as the “White Lot”). She provided fresh milk and butter to the Taft family for more than a year until one night in April 1910, when she died after gorging herself on oats she discovered in an open bin in the presidential stables.

Wisconsin senator Isaac Stephenson, saddened by the news, promised Taft the best-bred cow from his farm back in Kenosha County. The animal, named Pauline Wayne, was the daughter of the celebrated milker Gertrude Wayne, and was, wrote the Washington Post, “an aristocrat of the purest Holstein blood represented among the herds of the entire country ... valued at $1,000,” or about $24,000 in today’s money.

Pauline traveled in a special railway car to Washington, DC, and arrived on 3 November 1910. The Washington Post reported that a parade, complete with “a cloud of dairy wagons and hokey-pokey ice cream vendors,” was meant to receive her. But thanks to an erroneous telegram sent by Pauline’s chaperone, J. P. Torrey, the procession gathered at the wrong time—4 pm, instead of 4 am—and found itself confronted with an empty boxcar. (The Evening Star reported the incident somewhat differently, writing that Pauline’s railway car had been left behind in Pittsburgh, and that Torrey only discovered the mistake upon his arrival in Washington.)

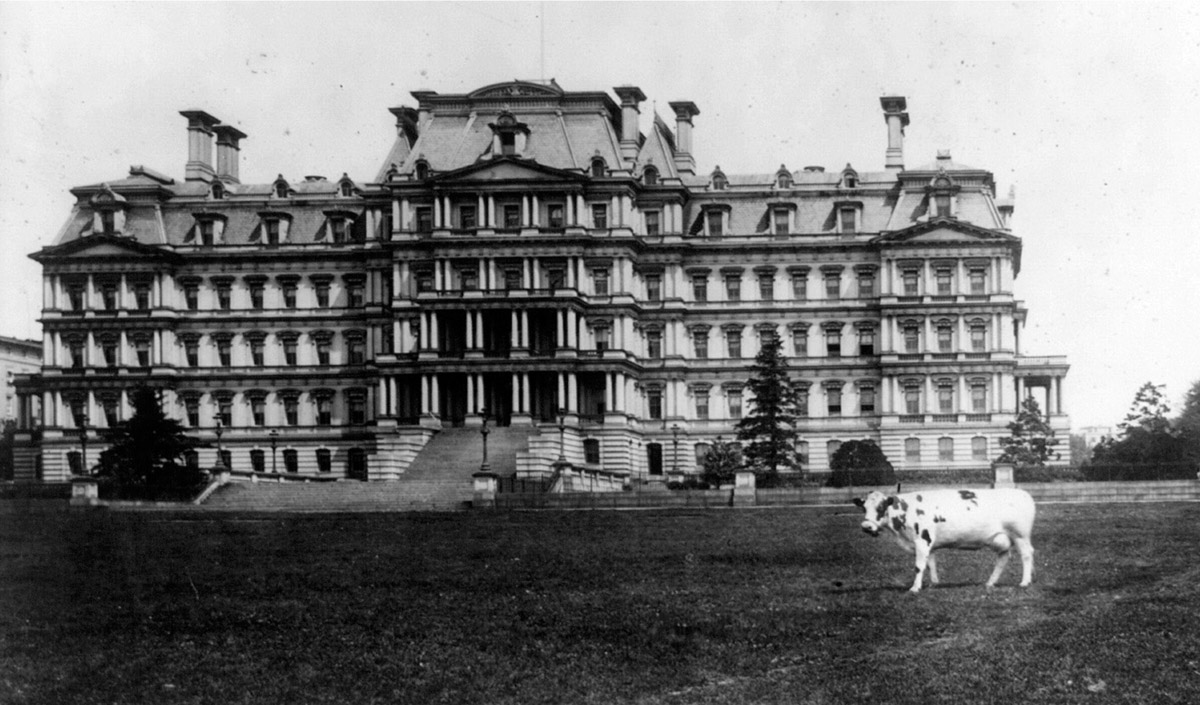

Like Mooley, Pauline—who the papers dubbed “Her Bovine Majesty”—was given free rein to graze Washington’s choicest lawns, including those of the White House, the Ellipse, and the State, War, and Navy Building, known today as the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. In 1911, she traveled back to Wisconsin to participate in the International Dairy Show in Milwaukee. Visitors could, noted the New York Times, buy “tiny” souvenir bottles of her milk for fifty cents, and a full gallon for five dollars (about $122 today). There are conflicting reports of Pauline’s daily yield, which in any case probably varied throughout her lifetime. The Evening Star claimed she produced up to nine gallons of milk per day and twenty-five pounds of butter per week. When she was on display in Milwaukee, the New York Times reported that she was producing sixteen gallons of milk per day and thus bringing in eighty dollars per day for the president. That figure was later corrected following a letter of complaint—the Times meant sixteen quarts, not gallons, meaning Pauline was producing a mere four gallons of milk each day.