Artist Project / A Pack of Blind Sniffing Dogs

We will not be collaborated with

Byron Kim

Addee: I just farted.

Lisa: Congratulations.

Ella: You win the Nobel Prize!

Ella (sniffing Emmett upon his return from a sleepover): You smell like Emilio.

Zane (Addee’s best friend, walking up the stairs at the start of a playdate): Something smells.

Addee: That’s my room. It stinks.

My family is obsessed with smells, especially our own. “You stink,” passes for a term of endearment in our home. Adeline (four years old and known as Addee) frequently holds her nose, not with her fingers, but by blocking the air passage through her nose with her glottis, a kind of olfactory denial. She does this most frequently during her long trips to the toilet which inevitably end with the announcement, “Daddy, Ibe dud!”, which means, “I’m done,” which really means, “Daddy, come wipe me.”

Adeline has a comprehensive term for the conditions that cause her to hold her nose. The word is “sniffy.” It has no direct correlative in standard English, though its first definition would have to be “stuffy.” The origins of “sniffy” can be traced to a warm day circa late spring 2000 in our cluttered sedan when baby Addee, firmly secured in her claustrophobic car seat, exclaimed, “Roll dowd by widdow! It’s sdiffy!” And so, after some minor translation, it was established that cars are sniffy, except in the dead of winter.

Sniffiness is synesthetic. It is essentially a sense of dwindling space brought on by warmth and stale odors. When I was asked to collaborate with my children for this issue of Cabinet, my mind immediately went to scratch ‘n’ sniff. What better way to bring smell to print? I thought I would turn the kids on to a bunch of unidentified scent samples and ask them to create visual counterparts.

Alas, scratch ‘n’ sniff turned out to be too costly. And as I tried to come up with another project, it was also becoming clear to me that the last thing I wanted to do with my children was some sort of “project.” I discovered this while working with Ella (six years old), who loved the idea of putting something in a magazine—who just loves making stuff, period. Whenever we set aside time to make something, it didn’t quite work. She tried her best, and that was just the problem. Our attempts were too intentional, too full of effort. I found myself foisting my ideas on Ella, and she, in turn, kept trying to make Art. For artists with one child, it often seems the child itself is a project, an object of artistic doting. Maybe these kinds of families can make art together, but with three kids, forget it. Again, the last thing I wanted was art, because everyone knows that what children do is especially beautiful because they aren’t really trying.

As I write this, I am in the middle of four weeks at UCross, an artists’ residency in rural Wyoming. I left New York a few days after school started; the day after I arrived was Addee’s fourth birthday. The next day was the first anniversary of September 11. The last of the sage bloom has put me in a histaminic haze. To the extent I can smell anything here in Wyoming, it smells too clean, altogether too aired-out. I miss my family, our sniffy, claustrophobic world.

My wife Lisa told me a few days ago that Addee has been saying that I am dead. Yesterday, I climbed about 450 ft. up to the top of a nearby butte (the only place I can get a strong phone signal) and asked to talk to her. Usually, a phone conversation with Addee lasts a matter of seconds before she gets distracted or her sister elbows her offline. Yesterday we talked a solid thirty-five minutes. I stayed on until she was good and ready, until I had been resurrected from the dead. She told me about her new pet fish Sweetheart (a birthday gift), about Kelly, her new best friend, about how she didn’t cry today after nap time at her new school, about Ella’s first piano lesson and latest soccer exploits. Mostly she wanted to know if I really climbed a mountain just to talk to her and did I really leave a message for her the other day from the top of that same mountain. And, of course, she was worried that I might fall off.

I have been hoping to work with the kids remotely. Asking them to send me their renditions of Sweetheart, the Red Fish. And especially trying to establish email correspondences with Emmett and Ella. Predictably, it isn’t working out. The new school year has its demands, and it’s becoming clear that my kids can sniff out and kill anything resembling a project with Pops.

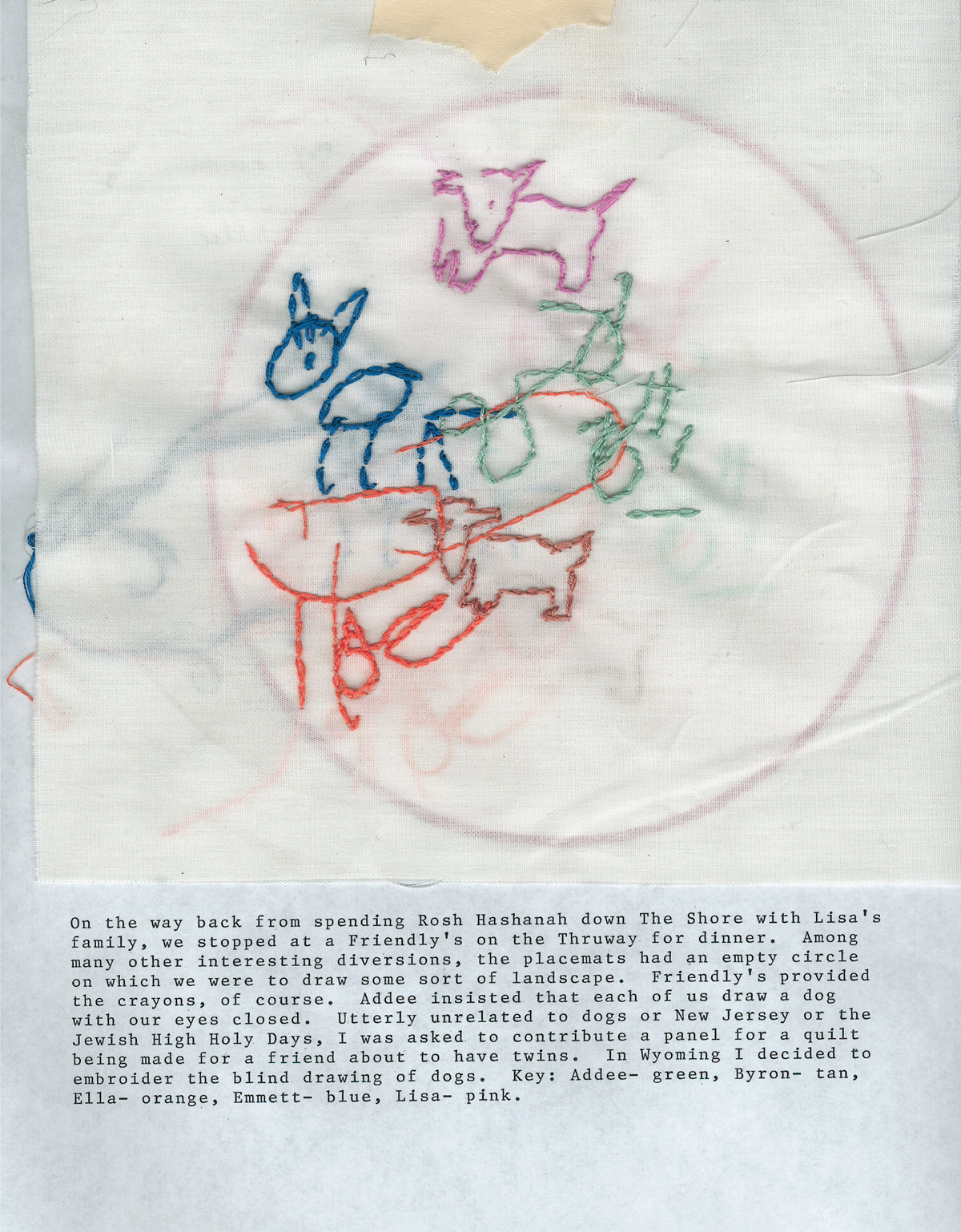

So this may seem like a cop-out, but my collaboration with Emmett, Ella and Adeline has turned out to be the same collaboration we have every day. We just follow each other around like a pack of Brooklyn waterfront dogs. It’s astonishing how much stuff our kids’ lives produce. Lisa and I throw virtually all of it out when they’re not looking. So I sniffed out a few choice scraps along the way and forwarded them to the magazine. I wonder what they’ll choose and I wonder if they’ll follow through on my request to toss the stuff once they’ve made 6,000 copies of it. All except for that fine piece of needlework I made. That shit is art.

Byron Kim is an artist with a studio in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Lisa Sigal (also an artist), Emmett Kim, Ella Bea Kim and Adeline Kim live with him in Park Slope.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.