Where the Wild Things Were: An Interview with Leonard S. Marcus

The history of children’s literature from Orbis Pictus to The Rabbits’ Wedding

Brian Selznick, David Serlin, and Leonard S. Marcus

Children’s literature—or more specifically, writing categorized as children’s literature—is often described as a benign (if often commercially aggressive, as in the case of the Harry Potter phenomenon) enterprise that revels in escapism and fuzzy feelings, offering a comfortable buffer zone between innocence and experience. But as Leonard S. Marcus, a leading authority on the history of children’s literature, describes, the history of children’s literature is complex and often contradictory, full of misanthropic philologists, modernist image-makers, and fanatical librarians.

Marcus is the author of Ways of Telling: Conversations on the Art of the Picture Book (Dutton, 2002) and Storied City: A Children’s Book Guide to New York City (Dutton, forthcoming 2003). David Serlin and Brian Selznick spoke with Marcus in September 2002.

Cabinet: Historically, is there a moment when “children’s literature” as we know it emerges as its own separate category?

Leonard S. Marcus: The work often cited as the first book written deliberately for children is a non-fiction book by Johannes Amos Comenius called Orbis Pictus, which was published in Nuremberg in 1662. It was a cross between a picture dictionary and a picture encyclopedia. There were little illustrations of things to be recognized, like a key or a dog, and the word that corresponded to the picture was printed along side it in both German and Latin. Thirty years later, in his Thoughts Concerning Education, John Locke wrote that children respond more readily to illustrated texts than to unbroken blocks of type. That observation became one of the basic principles for children’s literature. Orbis Pictus was a very popular book, and was published in the English-speaking world in the 18th century. In London in the 1740s, John Newbery was the first person to make children’s books a viable commercial enterprise aimed at the entertainment as well as the education of young people. Newbery was a printer, bookseller, publisher, sometime writer, as well as a seller of patent medicines, which was not unusual for the time since merchants very often had two or more trades. Newbery printed, published, and sold his own books, and commissioned writers like Oliver Goldsmith to write for him. More than Germany, England is where children’s literature as we know it got started. As the epicenter of the Industrial Revolution, England had the largest numbers of new middle-class parents who were eager for their children to be educated and get ahead in the world.

It sounds as if the emergence of children’s literature is roughly concurrent with the emergence of what we think of as the modern novel.

It’s interesting because we see a splitting off between what was considered “children’s literature” and what were considered appropriate kinds of storytelling for adults. For example, at the beginning of the 19th century in Germany, the Grimm brothers collected their very well known fairy tales. But the first edition was not published as a children’s book. The Grimms were not thinking of children as their audience; they were scholars. One of them was a philologist; the other was a librarian. They were interested in delving into the origins of Germanic culture, of recording it and capturing the part of it that was disappearing as Germany turned into a literate society. As sometimes happens, you publish a book with one audience in mind but it finds a different audience instead, and the Grimms’ fairy tales were received by the German middle class as a work primarily for children. The adults were not all that interested in reading about things that could never be, because they were very focused on succeeding in the modern world.

Scholars who study 19th-century literature often describe it as the “golden” period of the novel. Is there an equivalent “golden” or “classical” period of children’s literature among people who study children’s literature, or among children’s writers and illustrators themselves?

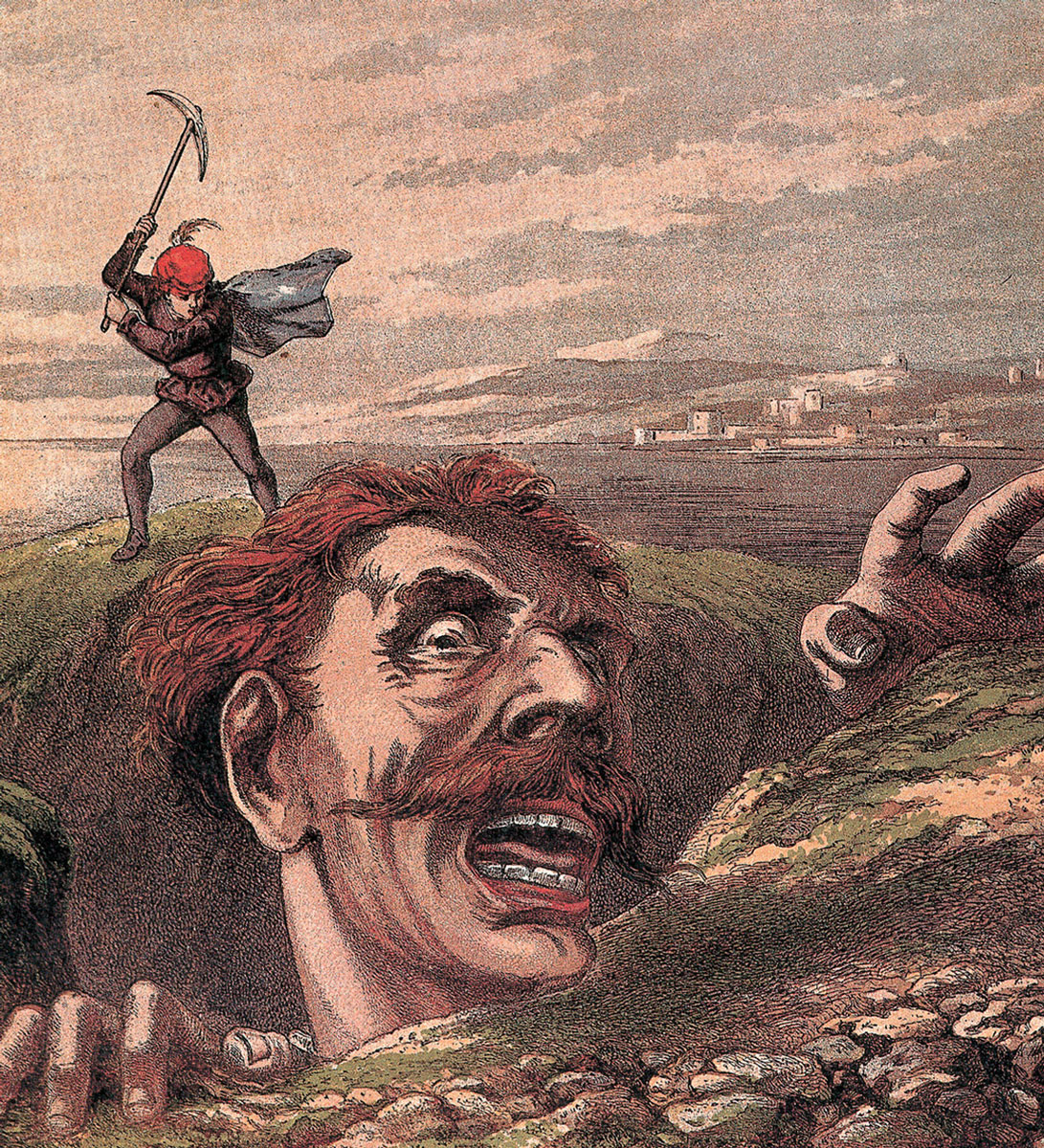

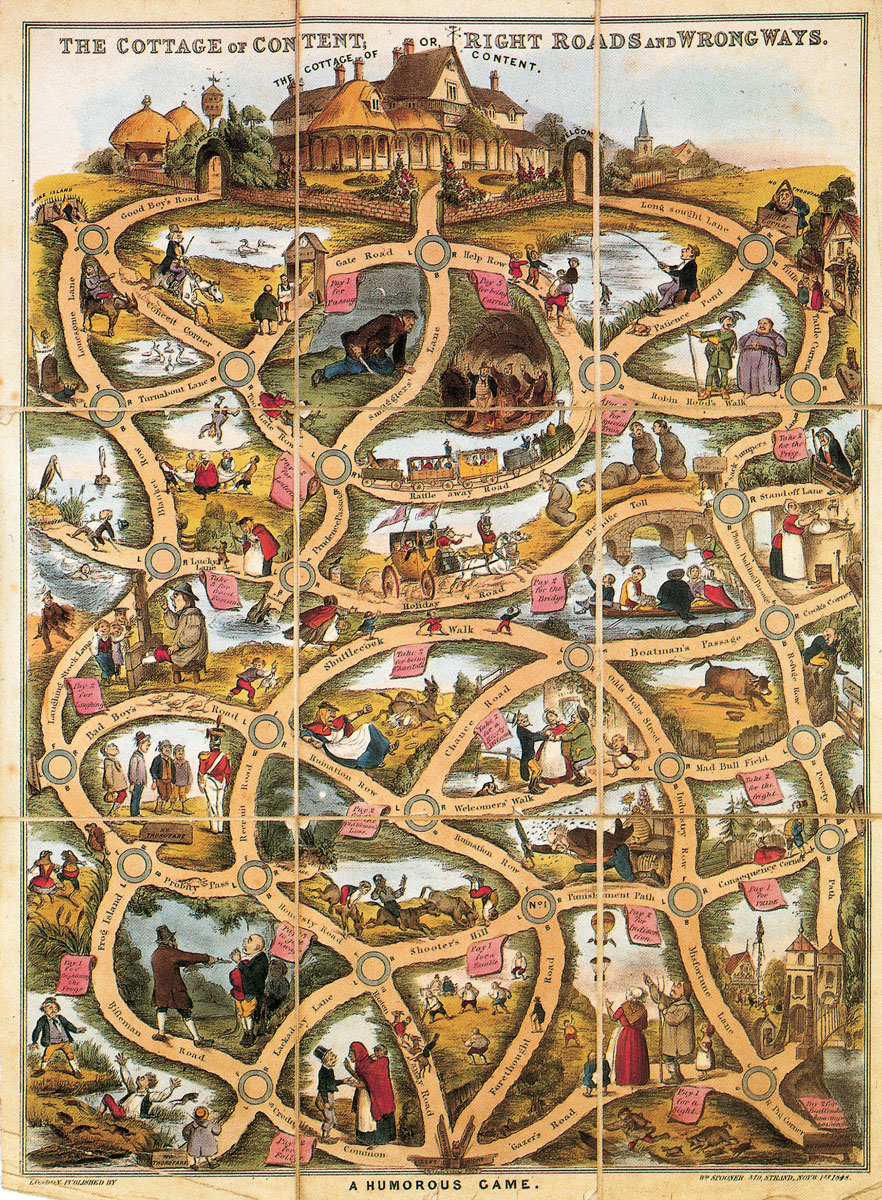

You can talk about different periods that were particularly good for the different kinds of books that fall within the larger category of children’s literature. In England, for example, Edward Lear published his Book of Nonsense Verse in 1845; in that same year, in Germany, the book known in English as Slovenly Peter, by Heinrich Hoffmann, was published as well. Lewis Carroll published Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 20 years later, in 1865. What those three authors had in common is that they were reacting to the didactic “how to be a good little boy or girl” kind of literature which was dominant at the time. They believed that children were reasonable beings and that perhaps what people most wanted at that time in their lives was a chance to laugh at and question authority, including their parents, teachers, and all of the people who stood over them. So the middle of the 19th century was a golden time for what is often called nonsense literature. For a variety of reasons, the mid- to late 20th century, in the US, turned out to be golden age of realistic fiction for children, and of the picture book.

Is there a connection or parallel development between theories of what kinds of books are appropriate for children and various theories about children’s education, child rearing, or child development?

You can trace a connection, all the way back to Comenius, between theories of education and the kinds of children’s books that were being published. In the early 1800s, Louisa May Alcott’s father, Bronson, ran an experimental school in Boston—until he was closed down for bringing in a black girl. Alcott was aware of the European theorists of education of his own and earlier times, and their ideas found their way into children’s magazines of the day with which the Alcotts were associated. You can trace the influence of those ideas directly to what happened in New York City starting in the 1910s at the Bank Street College of Education, which is where, among others, Margaret Wise Brown, the author of Goodnight Moon and many other picture books, got her training as a writer for children.

Edward Steichen was inspired by Bank Street to create two unusual photographic picture books for children. These books, although well reviewed, did not become especially popular in their time. The Whitney showed some of the photographs at an exhibit about ten years ago and has collaborated in the re-release of the one called The First Picture Book. There’s a clear resemblance between some of Steichen’s commercial work and his photographs for the children’s books. He was working from the Bank Street theory that one- and two-year-old children are most attuned to their immediate surroundings, respond to images of things they already know, and feel validated by the experience. He photographed toys, telephones, clocks—things that would be found in almost any home, in a straight-on way with a minimum of shadow. There’s no chiaroscuro effect going on; he was pretty much eye-to-eye with the object, placing each of those pictures across from a blank page that was left for the child to do with as he or she pleased. Nearly all contemporary “board books,” which are printed on durable cardboard for the very youngest children, follow from the concept and design of that book, whether knowingly or not.

There seems to be a relationship between the kinds of work that Steichen was doing for these children’s books and other kinds of modernist techniques or themes that we would identify in much more experimental, “adult” works.

That’s true. Steichen would photograph a seashell in order to reveal a universe in the swirls of the shell. Edward Weston would do a close-up of a machine to show that traces of the infinite could also be found in man and in the things of man. Of course, it’s also a major theme of 20th-century experimental art that the child is a kind of touchstone for seeing the world as it really is. The child as “primitive,” and the dream life of children, were ideas that mixed and merged in the minds of some of these artists. André Breton talks directly about children in his Manifesto, and claimed Lewis Carroll as one of the proto-Surrealists. Quite a few Magritte paintings appear to be based on scenes from Alice. When I taught children’s literature at the School of Visual Arts here in New York, I gave a slide lecture in which I “illustrated” Alice entirely with paintings by Magritte and Dali, M. C. Escher graphics, and collages by Max Ernst.

By the 20th century, there seems to be a split between those who want to create art to empower children’s imaginations and those who prefer to sentimentalize children as vulnerable beings who need protection from their own desires. Do you think that those two attitudes are in some kind of dialogue with each other?

That’s a good question. Around 1900, in the US, public libraries began to hire specialists in children’s literature and to open special reading rooms for children’s use. You can think of those rooms as “secret gardens.” They were walled off from the rest of the library. One reason why libraries created those rooms was to keep children away from the adult literature that they didn’t want them to have access to. If you think of the musical The Music Man, the townsfolk use “Balzac” as if it were a dirty word. The fear is that the children of River City are going to play pool and read Balzac and turn into lecherous, European-style perverts! The River City library was too small to have a children’s room, but that’s what was happening around the United States at that time. This had the effect of cordoning off children’s literature itself from the rest of literature. You find, after the turn of the 20th century, very few major literary publications showing any interest in children’s books, whereas in the 19th century The Nation and The Atlantic Monthly reviewed children’s books on a regular basis. But this is all a little hard to pin down. You’ll find one of the most powerful of the librarians—the New York Public Library’s Anne Carroll Moore—showing those protective and very proprietary tendencies some of the time but also loving a new children’s book by Gertrude Stein, which in 1939 was pretty far-out.

We know that there was a tradition of proletarian children’s literature in the former Soviet Union going back to the revolution. Was there a similar tradition of children’s books written by people in the United States who identified as socialist or communist?

Publishing was so connected to the library world, up through the 1960s and 1970s, that very often the editors at publishing houses were former librarians, and the largest part of the children’s market was the library market. So publishers were making books for the libraries more than for anybody else. There wasn’t a whole lot of interest in politically radical literature. In the 1940s, Jerrold and Lorraine Beim wrote picture books about friendship between black and white children, and did so from a consciously political perspective. The Beims’ career is pretty much forgotten now (and in fact their books have only an historical interest today, not a literary one). But their work filled a certain void.

An important children’s book editor of the 1940s and 1950s, Elisabeth Hamilton, was a pioneer in this regard and certainly was not politically naïve. She was trying to change society through the books she published, first as an editor at Harcourt Brace and then as the founding editorial director of the children’s book imprint at William Morrow. Hamilton’s father, Louis Bevier, had been the dean of Rutgers University during the time when Paul Robeson was admitted there, and he took Robeson under his wing. Hamilton published the Beims as well as North Star Shining (1946), the first children’s history of the “Negro” people, by Hildegarde H. Swift, and illustrated by Lynd Ward. Hamilton also discovered Beverly Clearly, so there is a really clear line of social concern.

Is there a connection between these kinds of works and some of the social realist books for young adults published in the 1970s like Dinkey Hocker Shoots Smack! or A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But a Sandwich?

The 1960s were a turning point for children’s literature. For one thing, it was then that most editors and librarians finally realized that most children’s books were about the life of the white middle class. An article in the Saturday Review of Literature in 1965 entitled “The All-White World of Children’s Books” caused a lot of people to think about what they had been doing. Until then, the children’s book world had been so self-enclosed, with middle-class book publishers selling their books to middle-class librarians. A few years earlier, in 1962, a picture book called The Snowy Day, by Ezra Jack Keats, had been published for very young children. It was set in Brooklyn and showed a little black boy walking out in the snow and having a great time. It had nothing to do with being black, but the fact that he had dark skin made it unique for its time. Other books followed, and suddenly picture books seemed, to a very limited extent, to become more integrated than before.

There was a new psychological realism in children’s books, too. Remember that it was during the 1960s and 1970s that psychology for the first time became a popular course of study at the undergraduate level. More people were finding it acceptable to go into therapy than ever before. It was against that background that the insights of psychology and psychoanalysis began to find their way into children’s books.

Can you give me an example of a children’s book that was directly influenced by psychoanalysis?

Well, Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak, for one. Having a story about a small child throwing a tantrum for the benefit of his mother was not a story you were going to find in children’s literature before the 1960s, because children weren’t supposed to yell at their mothers. The idea that children experience rage and that it’s a natural part of their psyche was a new idea to children’s picture books. This is why some people were afraid of Where the Wild Things Are when it was first published. It was initially quite controversial, a fact many people have forgotten since it was given the Caldecott Medal that year.

About a decade later, in a bizarre twist, Bruno Bettelheim condemned Where the Wild Things Are in his column in Ladies’ Home Journal as being too violent for children. He said that children of three and four would be too upset to be given a story in which another child was deprived of food. He thought it was a damaging story. I think these comments of his were more a reflection of Bettelheim’s confused psyche than of his theories. They don’t hold true to the central argument of his book The Uses of Enchantment, which was published not long afterward, in 1976.

How does the collector’s market for children’s books or the illustrations created for children’s books compare to the collector’s market for art and books in general?

Until recently there weren’t many collectors who took children’s books seriously – apart from those books from the more distant past. People didn’t attribute value to them, and were generally dismissive of the art and writing in children’s books. There was little awareness of a connection to the rest of art and literature. In the 1940s, a medical doctor living in Washington, D.C. named Irwin Kerlan began collecting original art from contemporary picture books and founded the Kerlan Collection at the University of Minnesota. In those days, there was no market for contemporary original art of that kind. An artist who met Dr. Kerlan and got one his fruitcakes for Christmas was very likely to feel like giving him the stuff just because he was someone who really appreciated it.

That’s hard to fathom, that the art from even a successful children’s book would not be recognized as even worth a nominal amount.

Well, think about art photography. In the 1950s, the Limelight Gallery in the West Village was the only gallery in New York City that sold photographs. You could buy the best photograph by Edward Weston or Ansel Adams for between 10-25 dollars. And the woman who ran this gallery had trouble paying her rent! So photography is another art form that used to be valued differently than it is now.

Is there a book that gets the gold star for being the most controversial, or among the most controversial, children’s book ever published?

Slovenly Peter, published in Germany in 1845, became one of the most popular children’s books in history throughout the world. There have been at least 600 editions of the book, as well as numerous parodies; it was translated into English at least three times, including once by Mark Twain. It’s a kind of litmus test—or perhaps a Rorschach test—in that about half the people who have read the book or had the book read to them as children think of it as hilarious, and the other half think of it as scary as hell. Slovenly Peter is either a cautionary tale meant to scare you into behaving properly, or it’s a send-up of a cautionary tale, and people disagree as to which of those two things it is. For that reason, it’s a very controversial book. I don’t know outside of Germany how widely read it is read anymore but for many years it was a book that was hotly debated.

Garth Williams’s The Rabbits’ Wedding is a picture book, published in 1959, about a black rabbit and a white rabbit who fall in love and get married in the end. Williams denied that he intended a message about racial matters but the book was banned in the south and for a while made international headlines. It’s kind of hard not to read it as an allegory. The Story of Ferdinand, published in 1936, was controversial because it came out during the Spanish Civil War and some people interpreted it as a pro-Franco fable advising, “Don’t fight! Don’t resist!” Again, the authors denied that they were commenting on the situation in Spain, but some people were convinced otherwise. Even Goodnight Moon was controversial. Many librarians hated it because there was no story, and for them a good picture book was one that you could read during story hour at the library to a hushed audience. Until recently, librarians didn’t want very young children coming to the library, so they weren’t very attuned to books for very young children. Some saw it as a list of words; they didn’t recognize it as having literary merit. Plus, it grew directly out of the Bank Street theories about small children being interested in their immediate surroundings as opposed to fairy tale, never-never land. It was one of the archetypal works that drew people to one side or the other in the debate about realism versus fantasy.

I think that often what happens with children’s books is a by-product of the distillation that is required to reach their primary audience. I was reading the fourth and most recent of the Harry Potter books out loud to my nine-year-old son and there’s a supernatural figure called Voldemort who is the center of evil in the book. We were down to the last forty pages of the book on September 11. The section we were reading turned out to be about the return of Voldemort, this violent, terrible figure rising up out of the ashes to come back and haunt the good guys. Without my intending it, the book seemed to comment on some of the things that were happening in the world just then. Obviously, the author couldn’t have intended this. But children’s books have a way of resonating with real experience in unexpected ways. And the children’s books we remember make sense in precisely that way.

Leonard S. Marcus is the author of Ways of Telling: Conversations on the Art of the Picture Book (Dutton, 2002) and Storied City: A Children’s Book Guide to New York City (Dutton, forthcoming 2003). He lives in New York.

Brian Selznick has written and/or illustrated many books for children, including The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins, which was awarded a 2002 Caldecott Honor.

David Serlin is an editor and columnist for Cabinet. He is the co-editor of Artificial Parts, Practical Lives: Modern Histories of Prosthetics (NYU Press, 2002).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.