Utopia Beneath the Waves: An Interview with Matthew Stewart

Narcis Monturiol’s submarine dream

Jennifer Liese and Matthew Stewart

“Fiery are my cares, / Toilsome is my cause / To know what hides unseen / In this mysterious sea.” Narcís Monturiol, the 19th-century Catalonian submarine inventor (and would-be poet), sought more than just shipwrecks and new species in the mysterious sea. Like better-remembered utopian socialists before him—Robert Owen, Henri de Saint-Simon, and Charles Fourier (who foretold the oceans turning to lemonade in a perfect world)—Monturiol sought to create an ideal society. How a submarine might aid this cause is the focus of Matthew Stewart’s Monturiol’s Dream: The Extraordinary Story of the Submarine Inventor Who Wanted to Save the World. Jennifer Liese met with Stewart in October to discuss Monturiol’s quixotic ambition.

Cabinet: Monturiol isn’t an especially well-known name. How did you discover him?

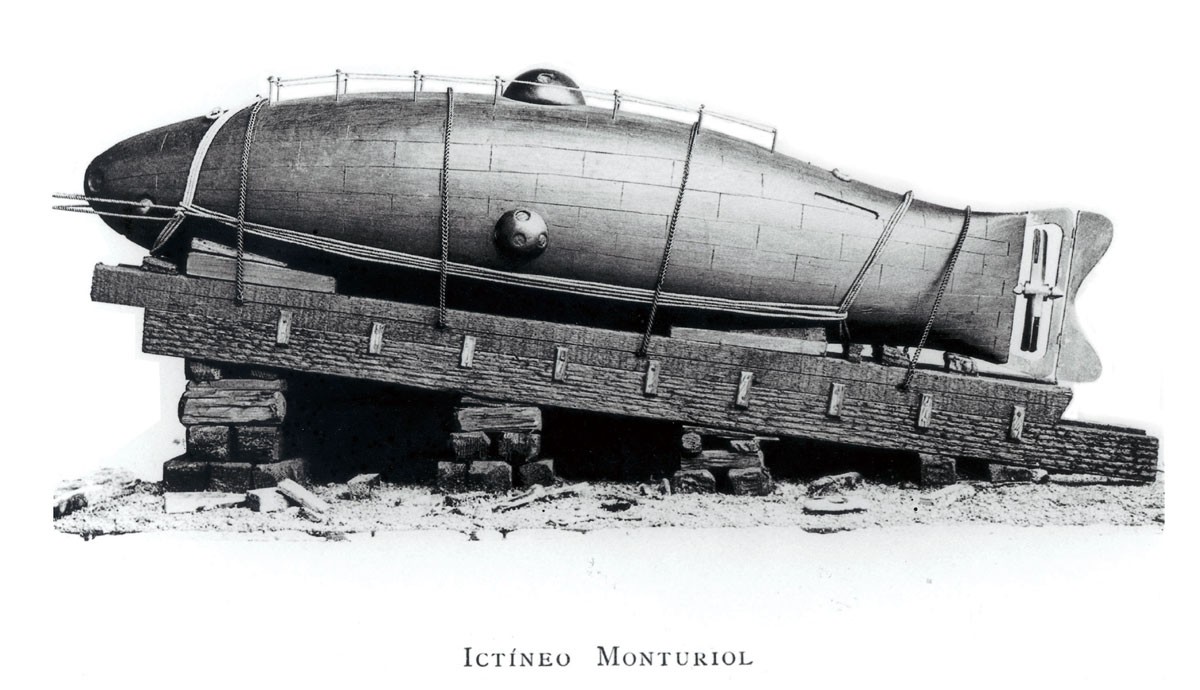

Matthew Stewart: When I was 11 or 12 years old, my Catalan grandfather told me that the submarine was invented in Barcelona. I was skeptical—he tended to say that all good things come from Barcelona. In the mid-1990s, I was walking along the new piers that were built for the Olympics and came across the refurbished model of Monturiol’s submarine. It’s near a Lichtenstein sculpture, so I actually thought it was just another artwork. But then I got up close and realized it was the submarine my grandfather talked about. For six or seven years, researching Monturiol was my hobby. Then I thought I’d share this passion with the rest of the world.

You call Monturiol the inventor of the first true submarine—what’s the distinction?

Some people make fun of me for calling it a true submarine. They say, “As opposed to a false submarine?” But he did build the first fully operational submarine. It was the first that could be maneuvered precisely and reliably at depths of 30 meters (Monturiol’s aim was to go to the very bottom of the deepest part of the ocean); it had the first non-human-powered engine for underwater locomotion; it had an air purification and replenishment system that allowed its crew to remain underwater indefinitely; and it came equipped with devices for interacting with the underwater environment. It was 20 years ahead of its time both conceptually and in terms of implementation; it included breakthroughs that weren’t again developed until the age of nuclear submarines. That’s why I’m willing to stick my neck out and have all the submarine aficionados chop my head off by saying that he really did invent the first true submarine. I don’t want to say that people like Robert Fulton, who built a submarine in 1801 before the famous steamboat, were unremarkable, but their aims were exclusively military. They were focused on building a device that would use the water as a shield to hide from the enemy warship just long enough to plant a bomb at the bottom. Monturiol’s idea is much more comprehensive and universal. His mission is primarily scientific and exploratory—the same inspiration that’s behind lunar projects. And when I put in the subtitle that he wanted to save the world, well, that’s no joke. He wrote that the submarine would solve the problem of living in the midst of chaos.

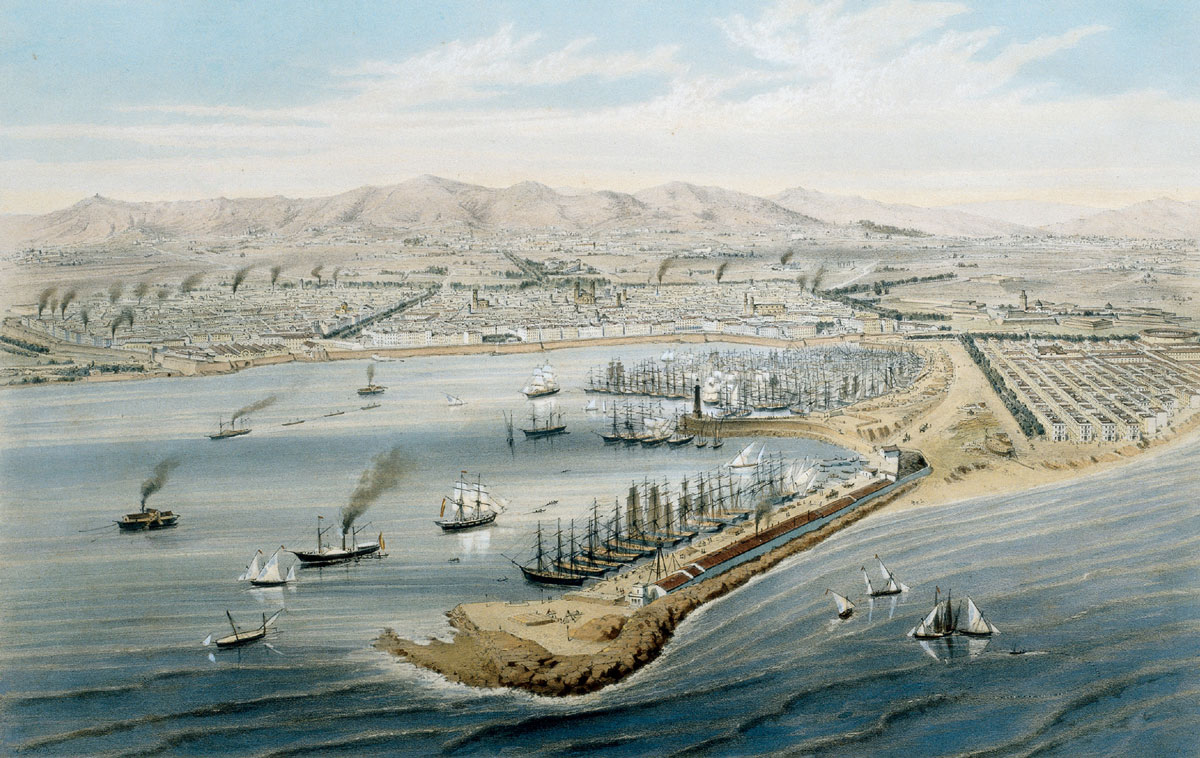

Catalonia was a particularly chaotic place in the mid-19th century. How did that atmosphere influence Monturiol?

Catalonia lost its statehood very early. It’s a culture that traditionally emphasized independent agriculture, but it was also the industrial heartland of the country. This led to some very unusual mixes. On one hand, you have people like the engineer Ildefons Cerdà, Monturiol’s friend, imagining strange modernist utopias. On the other, the ancient attachment to the soil expressed itself as a longing for a lost idyll. The relationship between Spain and Catalonia was also very problematic. In order to keep Barcelona from gaining too much power, the central government confined it to the medieval walls of the town—an incredibly effective tactic of oppression. As the population and the factories grew, life became just very nasty—low life expectancy, cholera outbreaks, child labor. These conditions fed a very strong left-wing movement, of which Monturiol was a part.

He ran a number of revolutionary journals when he was in his 20s and 30s.

That’s right. He experienced the typical evolution of a revolutionary. His first phase, from age 20 to 24, was a violent one. He participated in armed uprisings and became a captain in the militia. Next, he experienced a pacifist revelation, decided he just couldn’t stand to look at a gun anymore. And then he committed himself to working for change, but change through the press. So he ran a series of journals, each of which went through the same scenario: He’d get a group together, finance it, publish it, write a few articles about liberation, get shut down, then start up another one. My favorite is called The Mother of the Family.

He was a proto-feminist. He also argued for separation of church and state, for freedom of expression. Were these radical values for the time?

If you read the critical speeches he gave in his more mature period, he doesn’t sound very radical at all. He said, for instance, marriage should be licensed by the state and not by the church, which of course is the norm today, even though some people would like to change that. But you have to remember that at the time the world was much more theocratic. Spain in particular was not that different from contemporary Iran. When he said women should have rights, it was quite incendiary. Some aspects of his program were even kind of loony. For instance, he really believed that you could set up a utopia out in Texas.

It was Étienne Cabet who tried to do just that. What’s his place in this story?

We tend to think of communism through the lens of Karl Marx—as inherently based on violent revolution, on representing the interests of the proletariat against the upper classes. Cabet represented another strain that Marx completely squashed, a communism that embraced all of the classes, that was pacifist, and that ultimately attempted to create this new society in Texas. Cabet called it Icaria, and it eventually failed, but earlier on, Monturiol formed a society called La Fraternidad to support the Frenchman; he was deeply influenced by this utopian vision of earthly paradise.

You use two Catalan terms to describe Monturiol’s character: seny and rauxa. What are these traits about?

Seny I think of as reason with a little r; it’s basically practical sense or smarts and it kind of boils down to money. There are a thousand bad jokes about how stingy and miserly the Catalans are. Rauxa is the mystical, irrational side of Catalan culture. Catalans are quite accustomed to analyzing themselves and their own culture this way, so it’s not something I project on them. Monturiol is just an incredible representative of both put together. He built this submarine, an incredibly practical thing, full of seny, but one he thinks will bring perpetual peace. He’s a visionary, so the rauxa is always there.

Before the submarine, Monturiol’s most significant invention was a cigarette-rolling machine. What sparked the idea for his submarine?

One day, in his 20s, he was on the coast of northern Catalonia watching coral divers go about their business, a very hazardous business—shark attacks, getting caught on the coral, drowning, and asphyxiation were common. He saw a coral diver being pulled up on the shore, half-drowned, and according to a friend’s account, he helped rescue him. Sometime right around then, he came up with this idea of a self-contained vessel that would allow people to harvest coral safely. But he didn’t start building it for another decade or so.

So he began with a practical and humanitarian purpose. When did he invest the submarine with greater scientific and spiritual meaning?

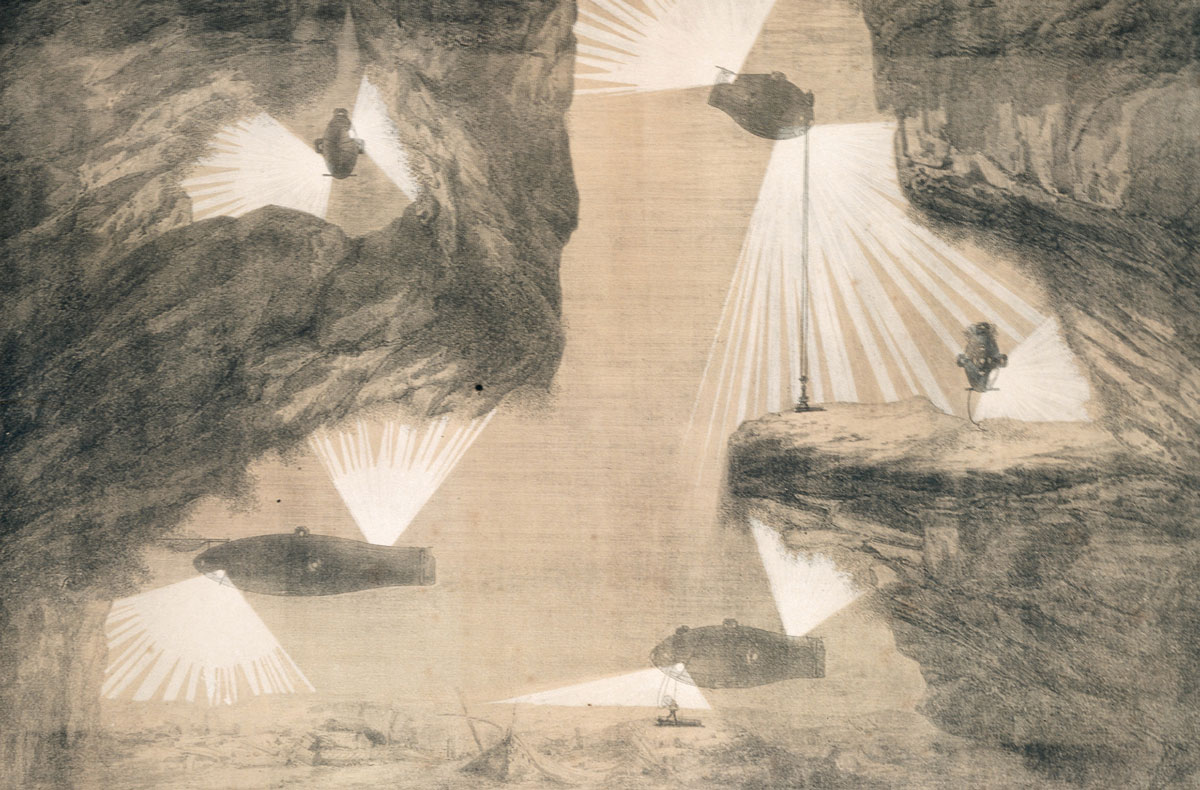

From the very first time he talks about it, he brings up the scientific mission. He was very much inspired by Alexander von Humboldt, the German scientist and explorer and an unparalleled synthesizer of natural phenomena. Monturiol read the many volumes of von Humboldt’s comprehensive Cosmos, which proposes that the purpose of mankind is to explore, to expand our knowledge, to broaden our world. This ideology fit perfectly with the submarine: According to Monturiol’s thinking, the submarine could expand our knowledge three or four times because there’s three or four times as much land under the water as above the water! So the scientific application for submarines was clear; Monturiol was a Jacques Cousteau of his day. But the link between the submarine and bringing about a utopia on Earth required many leaps of faith. I wouldn’t pretend that Monturiol could see the ten steps between the submarine and the perfect society. He’d be crazy if that were the case. I think it operated at a very abstract level in his thinking. It was not a direct cause and effect—you build a submarine and universal peace will come—it’s more, you build a submarine and by example it changes the world. A perfect self-contained environment might inspire the rest of the world to order itself in a rational way.

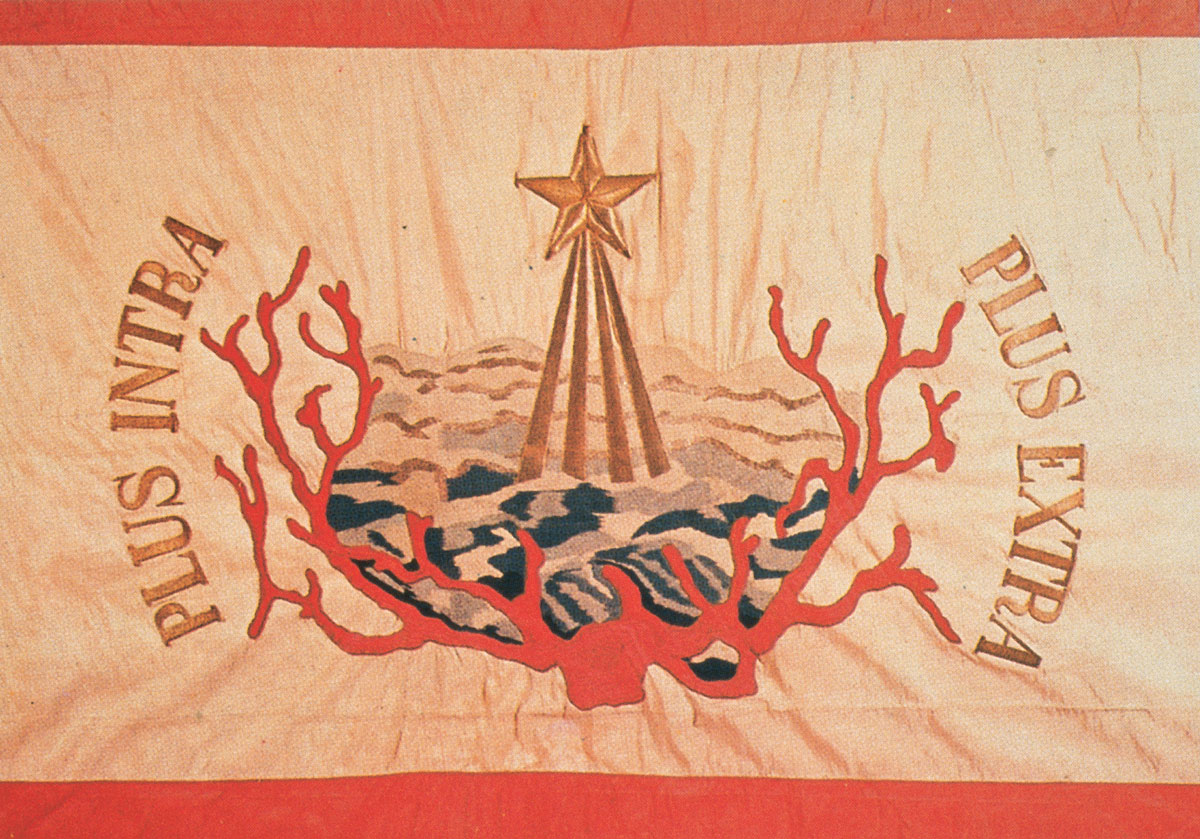

Monturiol built two submarines—Ictíneo I and Ictíneo II. What’s in the name?

It comes from ancient Greek for “fish” (icthus) and “boat” (naus). But, as Monturiol himself pointed out, the “neo” could also be taken as the Latin for “new.” So, he said, the Ictíneo is both a “fish-boat” and a “new fish.” That double meaning was actually very close to the heart of the project: At some very deep, quasi-rational level, Monturiol thought he was building a new species of fish. His project was metaphysical as much as it was physical.

Others before him—Aristotle, da Vinci—had imagined not fish-boats, but other submarine vessels. Who were a few of his immediate predecessors?

All kinds of curious characters had this idea of going under water for one reason or another, again, mostly for military purposes. Aristotle first suggested the idea of a diving bell, which is something like an upside-down bathtub, and scientists like Edmund Halley (of the comet) took him up on it. Some of the more relevant predecessors are David Bushnell, a young American revolutionary who built the Turtle, a one-man, hand-powered submersible built with the aim of sinking British warships. In terms of achievement, Fulton did the most credible job. He took his Nautilus down to depths of five to eight meters. One thing that’s clear from the early history of submarines is that this was a very risky business. Probably more than half of the world’s early submarines ended up at the bottom of the ocean, and in many cases left their crews there, too. The famous Civil War submarine, the Hunley, actually sank three times—and each time took its crew down with it.

What exactly were Monturiol’s technical innovations?

For starters, his submarines are so much more attractive. To look at the Ictíneo is a pleasure. Most other submarines were designed to look like surface ships: Just take the average ship and seal it up. Monturiol insisted that his submarine move as efficiently as possible under water: It had to be hydrodynamic. And that’s why he built it to look like a fish. That, interestingly, was an innovation that wasn’t appreciated until the era of nuclear submarines.

It’s funny, that seems so obvious to us. Diagrams of the Turtle show that it didn’t even swim the way a turtle would. It’s oriented as if it were standing on its tail, so it wouldn’t be hydrodynamic at all.

Before the 20th century, people didn’t think in terms of either hydrodynamics or aerodynamics. Things moved so slowly in the first place that you just didn’t think a flat surface would make enough of a difference to slow you down. Another crucial innovation was the double-hull—one inside the other—which would withstand the pressure of the deep. Monturiol insisted on a self-contained air-pressure system that would clear out toxins like carbon dioxide and also generate oxygen. He came up with a solution to securing portholes, making them in the form of wedges so that water pressure from the outside sealed them in. He also developed underwater illumination with a simple little gizmo that used hydrogen and oxygen to generate light. And the final, crucial innovation was the underwater motor. This was a big leap, and not just technically: Monturiol’s first submarine, like others before it, was human-powered—the crew sat on both sides of a crankshaft and turned a screw in the stern by hand. His second submarine would employ a steam engine. The problem here was that using fire to boil the water that powered the engine’s steam pistons would sap the oxygen from inside the vessel. Monturiol’s solution, which is really conceptually beautiful, was to find a chemical reaction that generates heat and creates oxygen. There are a thousand pages of his notes on chemical equations, but the one he ended up with uses manganese dioxide as a catalyst for potassium chlorate and zinc. In a way, Monturiol’s most important breakthrough was just in terms of performance and reliability. He submerged his first submarine 60 times and his second one several dozen times—with no loss of life, no injuries, and essentially no incidents at all. That’s an astonishing record when you look at what was going on at the time.

I imagine it wasn’t just luck, but Monturiol’s concern for humanity that made for such a clean record.

Exactly, if your purpose is to save the world, you can’t very well be killing people in your submarine.

Despite being an adamant pacifist, Monturiol eventually did appeal to the military for financial backing. Did this weigh on his conscience?

Ultimately, his dream of the submarine trumped everything else and he resolved away the dissonances. First, like a good communist, he tried to raise the money from the general public, a nickel at a time. But once he concluded that the only way to secure funding was to appeal to the military, he did that. There’s a manuscript in Barcelona’s Maritime Museum called Ictíneos of War. It’s brutal, like Leonardo’s fantasies about new weaponry. Monturiol designed this killer machine that would go down to a depth of 1,000 meters, carry 250 people. He argued that it would be used primarily for defensive purposes. He also claimed that it would be so potent it would end war and bring peace. Of course we’ve heard this argument many times, especially once nuclear weapons were developed.

Speaking of those, it’s not unheard of for something to be invented for beneficent purposes and then used toward horrific ends—Monturiol might have known he couldn’t have prevented the destructive use of the submarine.

Every technology has a military application. The broader issue is: What is the logic of history? How linear is history? Did the invention of the submarine have to happen at a particular time and in a particular way and for a particular purpose? To the extent technology is a function of one overriding goal—developing military technologies—and that in turn is the consequence of, say, the nation-state system or the organization of modern society, in a way it becomes inevitable that the submarine would be developed at this point and for this purpose. On the other hand, the Monturiol story, apart from this concession to the logic of history, is completely outside of history. No one would have predicted a submarine from Catalonia. No one would have expected that the man who invented the first true submarine was motivated by saving coral divers. The lesson of the story is that history is a lot more fragmented, and a lot less predictable, than we think.

Today there are only models of the two Ictíneos—what happened to the originals?

The first was hit by a ship while docked and destroyed. The second one got ripped apart in another way: In 1868, when Monturiol was just on the cusp of completing his dream submarine—one with an internal steam engine—he ran out of money and his creditors repossessed it. He had built the Ictíneo II before he had the engine figured out, so when he completed the engine, he installed it part by part inside. Because this engine was the only thing with resale value, the creditors tore the submarine apart to remove it whole. Not much else survived, unless you count the portholes, which the creditor used to decorate his own bathroom.

Monturiol must have been devastated! Without this material legacy, how does his influence persist?

Monturiol, I argue, had a lasting effect mainly through his friends at the end of the day. He built the most amazing submarine, but it was destroyed and the technology was not resuscitated until after other submariners had replicated it. So he really didn’t have an effect on the history of submarines, but he had a huge effect on the history of Barcelona through the people he inspired. There was the musician Josep Clavé—if you go to Barcelona today the people still sing his songs. Also Cerdà, who designed the layout of Barcelona we see today. And the famous poets and writers of the time—their vision, too, was very much shaped by Monturiol. The late-19th-century renaixença, along with the period of modernisme, is traditionally taken as the great flowering of Catalan culture. We all know Gaudí, who immediately follows Monturiol by not even a generation. I think there’s a strong case to be made that the rebirth can be dated to Monturiol’s efforts. Of course everyone who writes a biography thinks his hero changed the world.

I thought you avoided that claim quite admirably. With all the books out now about how this or that changed the world, you’re just saying your hero wanted to save the world. Ultimately, you tell a story of Monturiol’s redemption.

Yes, it is a story about redemption, and maybe even transfiguration, in an ironic way. The genre that comes to mind is tragicomedy. He died obscure and poor and completely neglected. So that’s the tragedy. But five years later, he’s resurrected, hailed in the press, and made a hero. That’s extremely representative of what goes on in Catalonian culture. Catalonia is a culture that lost its empire, so the country’s always been about loss. We always like our heroes to suffer and then we glorify them after death. There’s a kind of perversity—things are only good after they’re gone. In Catalan there’s a word for this—enyorança—which is like nostalgia, but it’s not just benign sentiment, it’s mixed with longing and pining. It’s a commitment to believing in the perfection of a past that will never under any condition return. Further, Monturiol is a case study in success and failure. I’m cynical enough to be skeptical of anything that’s presented as a great success, which is typical with inventions. Monturiol is a tremendous success and a catastrophic failure at the same time. He built a submarine, and yet he died impoverished, and yet he was remembered and had a tremendous effect on a culture.

At one point you write, “Progress sometimes depends on the unreasonable individual and the unreasonable dream.” It’s pretty uncanny that Don Quixote was Monturiol’s favorite book.

And for a short time he lived in the house where Cervantes died. Plus, if you look at the propeller on the back end of the submarine, it definitely looks like a windmill.

Matthew Stewart is the author of The Truth About Everything: An Irreverent History of Philosophy, with Illustrations. He has a doctorate in philosophy from Oxford University. He lives in New York City and is currently finishing a book on the relationship between Leibniz and Spinoza.

Jennifer Liese, who recently joined the editorial group of Cabinet and the staff at the Rhode Island School of Design, has written of late for Artforum, Bookforum, and TENbyTEN.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.