Inside the Mechanical Turk

Amazon’s microtasking platform and the question of stolen labor

Cabinet

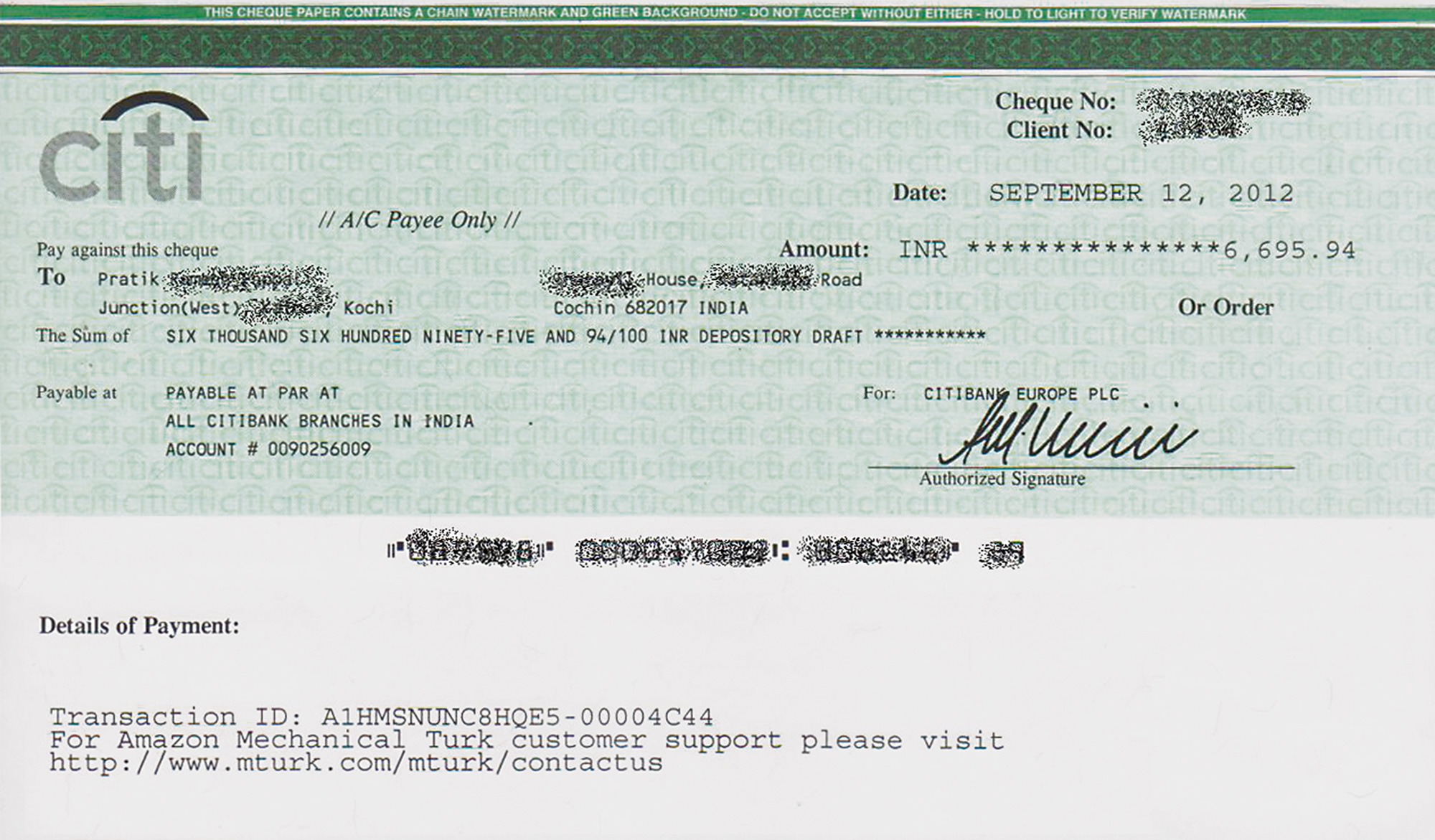

Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk platform is an online labor “exchange,” debuted in 2005 by the Internet retailer, in which individuals contract to perform various tasks for others at an agreed-upon rate. Named, with an improbable amount of historical flair, for a celebrated eighteenth-century device—purportedly an extraordinarily skilled chess-playing automaton, it was later found to have in fact been operated by a human player secreted inside the cabinet behind which it sat—the modern-day Mechanical Turk is “a marketplace for work that requires human intelligence,” according to Amazon. The platform “gives businesses access to a diverse, on-demand, scalable workforce and gives Workers a selection of thousands of tasks to complete whenever it’s convenient.” These tasks range from data entry, cataloguing, and transcription to identifying image details, serving as survey subjects, and the like: most are activities that humans do better than machines, most take between a few minutes and a few hours, and all are compensated at exceptionally low rates. The wages offered for the fifty most recently posted HITs—Human Intelligence Tasks, in Amazonian parlance—on the late November afternoon in 2015 on which we are writing this, for example, range from a high of $2.50 (playing an online multiplayer game and then responding to a survey on it) to a low of $0.01 (more than a dozen tasks, from finding phone numbers and email addresses on a web page to copying down all the purchases on a printed receipt). Amazon charges “requesters,” those with available jobs, an additional fee of 20 percent on each transaction. According to its website, there are more than half a million workers in over 190 countries standing ready to take on the 442,274 tasks currently on offer.

It’s been roughly a decade since the widespread emergence of large-scale computer-supported work platforms, and labor scholars and policy analysts from bodies such as the Geneva-based International Labor Organization have increasingly begun to turn their research efforts toward the conditions of participants in so-called crowdsourced labor environments.[1] Interested to learn for ourselves what the men and women at work “inside the box” thought about the labor they were performing, Cabinet signed up to become a requester and posted the following HIT (directed at US workers because tax laws here make it very complicated to employ foreign freelancers):

Please write an essay of 300–500 words about whether labor can be stolen or not. Do you feel that your labor has been stolen on occasion? Do you feel that this assignment is itself a form of theft, or does the fact that you have taken this assignment mean that it is, by definition, a fair, equitable exchange? Be honest. What we are offering is equivalent to the mini